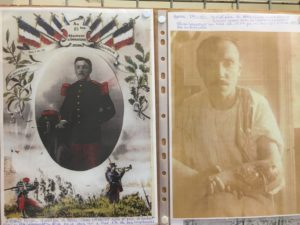

In the photo on the left, a young mustachioed French soldier from a century ago is dressed in his parade best as he stares coolly at the camera. His left hand is behind his back and his right rests on a table, near his red kepi and what might be a bayonet. It is the kind of photo young men posed for, ahead of going to war, in 1914.

The photo on the right shows the same soldier, with the same mustache and the same cool regard for the camera, apparently sitting on a bed … a hospital bed, it would seem … and he holds his bare left arm across his chest. The observer cannot help but notice that his arm is horribly swollen.

The soldier’s name is Marcel Poujol, and he would lose his burned arm to amputation. But he may have considered himself lucky, three times over.

He survived a shell that killed most of his comrades. He would not be going back to the trenches of what the French call La Grande Guerre — the Great War — to become one of the 1.4 million French war dead. And he would be able to live and work in his hometown of Nizas, in the Languedoc region of southern France, raising a family that includes his living granddaughter, our friend Marie-Claire.

The photos of Monsieur Poujol are part of a large exhibition assembled by local historian Guy Abellanet, 76, at our village’s salle de fete ahead of the 100th anniversary, tomorrow, of the Armistice of November 11, 1918 — which ended the fighting in what Americans usually know as World War I.

The war was a disaster for the European continent, killing 9 million combatants, maiming or injuring many more, creating a gender gap that could be felt for decades and impoverishing four countries (the UK, Germany, France and Italy) that in 1913 had been among the top eight economies in the world.

The war brought down three empires (the German, the Austro-Hungarian and Russian) redrew maps, carved out new countries and created an unstable peace that led almost inexorably to World War II, two decades later, which killed even more Europeans, most of them civilians.

Abellanet, an assistant mayor in Nizas, is displaying his personal collection of posters, newspapers, political tracts and, of most interest to residents in town, letters and photos of several soldiers whose families still live in this town of about 650 residents.

Twenty-two men from the little town died in the war, including three brothers from a family named Hot (pronounced Oat) and two from a family named Lauriac. The Hot family seems to have left the region, but survivors of the latter family still live in town.

Among the correspondence on display is a lengthy letter from a middle-aged solider named Dieudonne Bedos. He scolded relatives for not having responded to his previous letter and described what he was doing near the killing fields of Verdun, in northeastern France.

He was involved in digging a tunnel under the lines, and he wrote that he preferred to be underground than up above, where death-dealing shells and bullets flew.

Not long after his letter, however, the tunnel was hit by an explosion that incinerated more than 600 men, including M. Bedos.

The whole of the display is eye-opening; it gives a good sense of just how terrible the war was and how it destabilized much of Europe just as the continent had reached its zenith as societies — art-loving builders and educators who were inventive and optimistic.

By the end of the war, France was exhausted, essentially broken and bleeding.

Monsieur Abellanet readily concedes that without the U.S. intervention in 1917, France would have lost the war.

He noted some accomplishments: France regained the departments of Alsace and Lorraine, lost to the Germans in the previous century; France took (brief) control of part of Syria and several African nations, as well.

But, he said, “winning” the Great War offered little consolation to those who lost loved ones in the bloody fray, many of whom will be remembered on Armistice Day tomorrow, when Nizas turns out for a parade to the war memorial erected in 1921 and inscribed with the names of the dead.

It will be a somber event.

“It’s a sad day,” Abellanet said. “You celebrate the victory, but you celebrate it on a ground filled with the dead. Not a real victory.”

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment